The Best Of Fad Gadget was originally released in 2001 to accompany Frank Tovey bringing his Fad Gadget alias out of retirement for a support slot with Depeche Mode. It was a moment of electronic music history repeating itself, albeit in reverse and on a massive, stadium-friendly scale: Depeche had supported Gadget in 1980, back when they were all a bunch of callow, synth-loving young chaps, Frank Tovey being the first artist to join Daniel Miller’s nascent Mute Records.

Twelve months after the compilation was issued, Tovey was dead from a heart attack. It’s hard not to listen to these tracks, hand-picked as they were by Fad himself, without mourning the fact that he left behind such a brief legacy – a clutch of singles, four Gadget albums and a challenging performance art repertoire that was already honed back when he was fighting over Leeds Polytechnic’s studio space with fellow students Dave Ball and Marc Almond.

Mute’s pressing of the album on vinyl for the first time coincides with the fortieth anniversary of ‘Back To Nature’, Fad Gadget’s first single. Recorded with Daniel Miller, ‘Back To Nature’ nodded to the Ballardian tropes of Miller’s own ‘Warm Leatherette’ statement, but also highlighted Tovey’s wry humour: while its gloomy industrial electronics sounded like a post-apocalyptic world of extreme temperatures, it was in fact Tovey ruminating on sun-loving folk enjoying the beach at Canvey Island.

Its B-side, ‘The Box’, was yet more subversive, its desperate lyrics reading like the stage directions for a macabre one-man show with a performer stuck in a box. After the dry ‘Ricky’s Hand’ single – the sinister counterpart to Depeche Mode’s similar-sounding ‘Photographic’ – Tovey gently moved Miller’s producer’s hand to one side and forged his own path, his 1980 debut album Fireside Favourites dealing with everything from cosy nights around the hearth during a nuclear meltdown on its memorable title track to bedroom frustration, each track a symbiosis of Tovey’s synths and whatever potential sound-making objects were lying around the studio at the time.

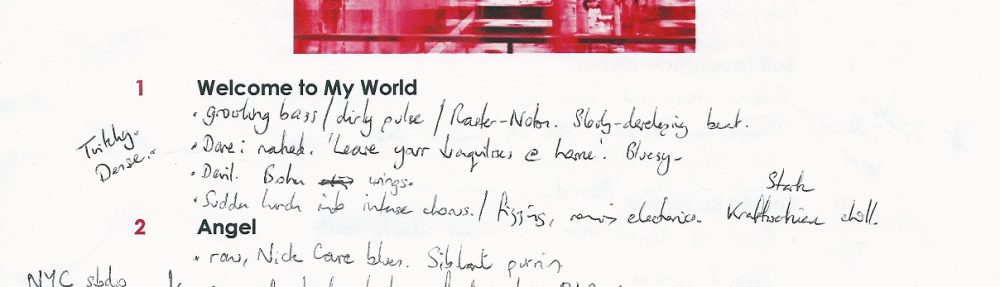

Through his ensuing albums – Incontinent (1981), Under The Flag (1982) and Gag (1984) – Tovey developed his songwriting craft, initially through getting to grips with kit like an MC-4 sequencer and then developing a full-band aesthetic at precisely the same time as pop music was dispensing with traditional instruments in favour of keyboards and drum machines. But even as his music matured, anticipating the series of folk and rock-inflected albums released under his own name with the band The Pyros, Tovey was still covering himself in tar and feathers on stage, or stripping off his clothes and spraying shaving foam all over his body, memorable images of which Anton Corbijn captured for Gag and the harrowing cover of this compilation.

His songs never once lost that slightly disturbing potency that had made his earliest singles so insistent. ‘Lady Shave’ made a song about the quotidian act of removing hair a seedy, voyeuristic, perverted show; ‘Saturday Night Special’ dealt with guns and the right to bear arms; ‘Love Parasite’s sleek electronic shapes detailed a sexual predator; ‘Life On The Line’ and ‘For Whom The Bells Toll’ were dour pop songs that betrayed Tovey’s paranoia at having become a father for the first time; ‘Collapsing New People’ took industrial percussion and the looped mechanical sound of a printing press to offer a vivid anthropological assessment of the dispossessed, wasted, vampiric youths he observed while recording the track in Berlin. The compilation ends with the leftfield proto-electro and howling baby sounds of ‘4M’, sounding somewhere between clinical fascination and the soundtrack to the end of the world, but was in fact a tender piece of sound art using the sampled voice of his baby daughter.

It would, perhaps, be too easy to look back on Frank’s wild Fad Gadget years as a kind of grim novelty cabaret sideshow schtick, a product of an anything-goes, disaffected, post-punk British society, his effect on the development of electronic music in the early 1980s easily dismissible in favour of dark-hued works by Cabaret Voltaire, Human League, Soft Cell and others. Observed in hindsight, no other musician managed to fuse art school theatrics and dystopian social commentary so fluidly within the emerging constructs of electronic technology as Frank Tovey did, and the likelihood of another artist like Fad Gadget emerging in these supposedly super-liberal times is unimaginable; we’re all trapped inside the metaphorical cage of ‘The Box’, and no one dares try – like he did – to break out.

Frank Tovey: 8 September 1956 – 3 April 2002

The Best Of Fad Gadget by Fad Gadget was originally released in 2001 by Mute, and reissued as a double vinyl LP in 2019.

Words: Mat Smith.

Note: this review originally appeared in Electronic Sound issue 57 and is used with the kind permission of the editors. Thanks to Neil, Zoe and Paul.

(c) 2019 Mat Smith for Electronic Sound