At least as a concept, the idea of two musical legends – though operating in two vastly different, and arguably incompatible arenas – coming together as on this EP has the capacity to make the hairs on your neck stand to attention.

Edward Kennedy Ellington, better known as Duke, was undoubtedly the most famous big band leader. From 1923 until his death In 1974, Ellington presided over a body of work that encompassed so many memorable tunes that it sometimes feels like no-one else ever bothered to write a standard while he was around. Although generally written for his orchestra, it’s remarkable testament to the quality of Ellington’s compositions that they sound just as good performed by a smaller group (see The Dave Brubeck Quartet’s Newport Jazz Festival recording from 1959 for proof); heck, even The Wiggles had a crack at an Ellington tune, giving rise to the possibility that a generation of post-millennials might be switched on to swing era influences rather than abysmal pop music.

Despite learning his chops in venues like Harlem’s Cotton Club, places synonymous with jazz music, Ellington never considered his music jazz – he just thought of it as great American music, and that’s exactly what jazz is.

If the Duke was a compositional genius, Konrad Plank was similarly gifted in the environment of the recording studio. The artists he worked with is nothing short of awe-inspiring, taking in the likes of Kraftwerk, DAF, Brian Eno, Eurythmics, Neu!, Ultravox, Can, Devo and countless others. From 1969 until his untimely demise in 1987, Plank had worked across genres ranging from prog rock, Krautrock, the earliest forays into synth music within popular music, and even developed a type of proto-techno in collaboration with Dieter Moebius. His studio just outside Cologne was legendary, as was his prowess as an engineer.

DAF’s Gabi Delgado, who I interviewed last year for Electronic Sound gave me some insight as to just how important Plank was in the development of the gritty Deutsche Amerikanische Sound. Plank thought that the humble Korg that DAF brought to the studio was far too tinny and plastic-sounding, so he found a way to capture the natural sound of the synth via bass guitar distortion pedal effects, captured live in his studio via normal ambient mics. The result was something more edgy, but also more naturalised. Not quite like the aural fullness from a big band like Ellington’s, but certainly more human than the Korg without any help.

So, two legends, operating in vastly different and seemingly incompatible fields. Aside from working on sax giant Peter – father of Blast First artist Caspar – Brötzmann’s More Nipples album, jazz was notably absent from Plank’s repertoire, and aside from a bit of electric organ, Ellington’s music was pretty pure. The idea of Ellington asking Plank to make his orchestra sound dirty was never going to happen. And yet here we find Ellington, in July 1970 and toward the end of his career, working in the very studio out of which Plank was already carving a very distinct niche.

In truth, it could have been any studio in Cologne. Ellington was a furiously active composer, always trying out new ideas right to the bitter end, and so it wasn’t uncommon for him to usher his band into any available studio to work through new material, typically with little notice. Therefore the recordings of these two pieces – ‘Alerado’ and ‘Afrique’ – at Plank’s place were only made because his studio happened to be free for Ellington to rehearse in, because Plank’s rates were low, or because it was big enough to house Ellington’s band. Studios are commercial enterprises, and Plank was no different in this regard. There’s a fine line between struggling for your art and the breadline.

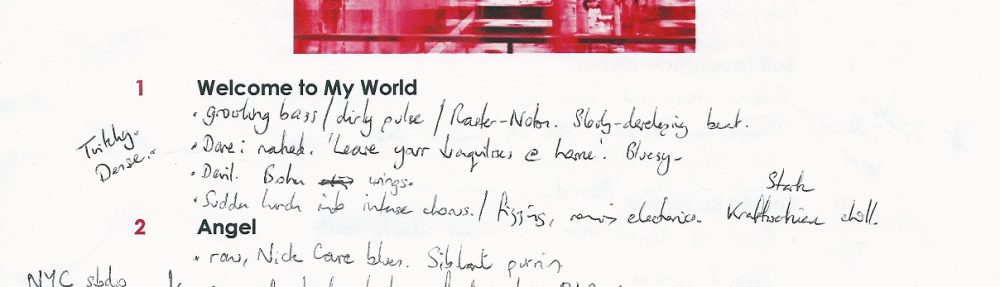

Critics have commented that the key level of intrigue in this release lies in being able to see Ellington’s compositional methods at close quarter. Both ‘Alerado’ and the drum-heavy ‘Afrique’ have appeared elsewhere on Ellington collections, but here we’re presented with three different takes of each piece, each of which subtly varies in terms of either arrangement, the tempo or duration. That said, to the untrained ear, both sound pretty complete on the first take (with the possible exception of how prominent Wild Bill Davis’s organ is on ‘Alerado’; it’s much less conspicuous by the final take), but when you contrast the third take with the first they sound world’s apart in terms of exactness. Ellington was a perfectionist of the highest order, and this confirms it.

He was also trying out a slightly reconfigured band after the death of his go-to alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges and a couple of new recruits, trying out flugelhorn player Fred Stone and putting in a rare flute solo; to an Ellington newcomer it will just sound like a big band going through their paces, but it was in fact Ellington constantly reimagining his orchestra.

Less obvious, but equally important, is that these recordings indicate how naturally accomplished Conny Plank was, even at this early stage in his studio career. Being able to engineer and record a full big band orchestra is a skill usually only reserved for the most specialised studio boffin, usually at cavernous mega-studios like Abbey Road. Assuming that Plank did engineer these sessions rather than just renting out his studio space for another hand to curate proceedings, it shows him to be just as adept at capturing a huge live band as he would do with smaller set-ups or where a lot of the action could be achieved on his side of the mixing desk, or with a recording like Eno’s Music For Airports which was barely there in comparison with the full sound that Ellington bashed out.

There’s undoubted curiosity value here whichever way you look at it. Just don’t go expecting to hear some radical reworking of a trademark sound. This is Ellington doing what he did best, and Plank more than proving his worth in the environment of a studio that would never again see quite so many players arrive en masse.

(c) 2016 Mat Smith / Documentary Evidence