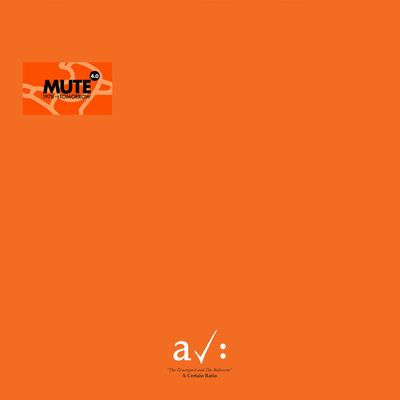

As part of Mute‘s fortieth ‘anti-versary’, the label is making available very special limited edition vinyl versions of selected releases from their four decades of releasing and curating incredible music. Full details on the releases can be found here.

“All the energy of Joy Division but better clothes,” is how Steve Coogan, playing Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, described A Certain Ratio in the 24 Hour Party People movie. Whether Wilson said it or not is obviously debatable – though it sounds like the kind of thing he would say – but it rather did the band something of a disservice. Joy Division may have been poster boys for Wilson’s experiment in running a label (badly), but aside from both hailing from around Manchester, arising out of punk, sharing producer Martin Hannett and being signed to Factory, there’s very little that ACR and Joy Division had in common; but then again, Wilson was never one to let the facts get in the way of a decent quote.

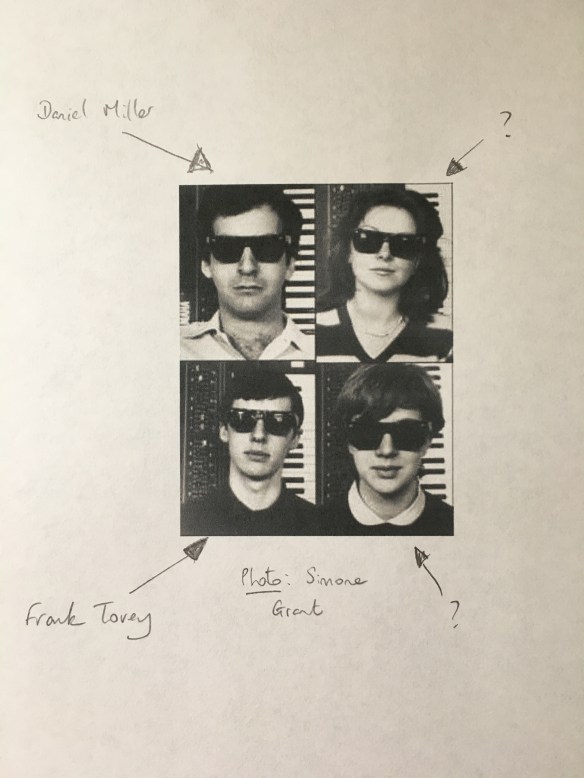

ACR were formed in either Flixton or Wythenshawe in 1977, taking their name from a Brian Eno song. The Graveyard And The Ballroom was rush-released by Factory on cassette in January 1980, and consists of a side’s worth of Hannett-recorded demos from Graveyard Studios in Prestwich and a handful of live tracks recorded at Camden’s Electric Ballroom when ACR were supporting Ian Curtis and crew. As was the case with most Factory releases, Peter Saville designed the sleeve, though on this occasion he wasn’t credited. As a debut LP release, hitching together demos – presumably of tracks ACR had been gigging for a while – with live tracks is a curious one, and the band would only record their first album proper – To Each… – in 1981. The curiosity of its release aside, it nevertheless perfectly captured that energy that Wilson may or may not have spoken about.

In 1979, ACR were a five-piece group of Martin Moscrop (guitar / trumpet), Jez Kerr (bass / vocals), Donald Johnson (drums), Simon Topping (keyboards) and Peter Terrell (guitar). As evidenced on the seven live tracks that made up the B-side of the tape, ACR might have come out of punk, but their music was much more honed than might have been expected. Together, as heard on tracks like ‘Oceans’, they made a tight, very precise sound, genuinely worthy of the often-used punk-funk tag. During that track’s extended instrumental sections you can hear a sense of refined musicianship coming through, each player fluidly interacting with one another in a manner best observed among jazz groups. In Jez Kerr the band had a singer who eschewed the nasal, I’m-not-really-a-singer traits of most post-punk vocalists, possessing a soulful streak on the looser, more open-ended, jazzier tracks like ‘The Fox’ as opposed to a period snarl. The side opens with the sinewy ‘All Night Party’, ACR’s first single, with its manic, intensely irrepressible rhythm section, being all the more remarkable as a live track for originally not having a drummer on it at all when Factory issued it earlier in 1979.

The Electric Ballroom tracks were recorded from the mixing desk by Tony Wilson in October 1979, just over a month after Hannett oversaw the Graveyard sessions. If it’s possible for a band to develop and grow into their sound in a mere month, A Certain Ratio did that, and some. The demos are raw and sludgy, bereft of Hannett’s mystic prowess behind the mixing desk.

What they have though is a latent quality, something itching to get out, as exemplified by the controlled sound of ‘Flight’ compared to its longer, more flexible live rendition. It’s the only track from the studio sessions to make it to the Ballroom set, suggesting that either ACR had jettisoned most of these tracks in favour of an entirely fresh new batch of much better material, most of which would end up on To Each… Nevertheless, amid the seven studio tracks are some real gems, such as the edgy, wistful ‘Crippled Child’ or opener ‘Do The Du (Casse)’ and ‘Choir’, both of which seem to owe as much of a debt to Stax soul or Motown as they do the Sex Pistols.

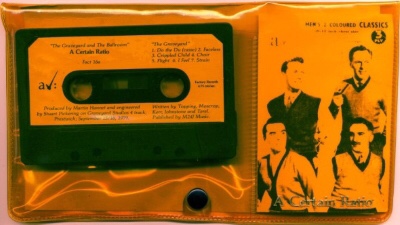

In the years after Factory’s sloppy collapse, several labels – chiefly Creation and Soul Jazz – have had a crack at reissuing The Graveyard And The Ballroom. Mute began working with ACR in 2017, becoming custodians of the band’s entire catalogue across the several labels they’d found themselves on over the years, as well as presenting brand new material. It found the label doing precisely what they’d done for the likes of Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire before, drawing a band’s entire body of work together under the careful jurisdiction of a genuinely artist-first imprint. For this album, Mute created a vinyl edition that linked back to the 1979 release, lovingly packaging the LP in a green PVC sleeve reminiscent of one of the versions of the the pouch that held the original cassette.

For Mute 4.0, The Graveyard And The Ballroom is being reissued as an orange LP edition in an orange PVC pouch, just like the original Factory cassette.

(c) 2018 Mat Smith / Documentary Evidence