Milton Keynes Gallery, 11 October 2018: after meticulously setting up in front of the audience, and removing his shoes, violinist Billy Steiger is nowhere to be seen. He has disappeared into an antechamber to the left of where I’m sitting, coaxing sounds from a metal music stand that he moved there earlier. It is a curious effect, these naturally reverberating, occasionally uncomfortable metallic, unamplified resonances emerging from a place that isn’t where your eyes are naturally trained.

After a while, though these sounds are far from predictable, you find yourself adjusting to the noise, leaving you just with your thoughts. After his set concludes, he takes up position on the opposite side of the performance space from Daniel Blumberg and his headless black Steinberger guitar, the intense form of double bass player Tom Wheatley between them. The trio run through songs from Blumberg’s Minus opus and songs that are inextricably of the same source as Minus but unfamiliar, including one track – ‘Off And On’ – that they play twice, both versions as different from one another as they are similar. As is Blumberg’s preference, the audience is not given the opportunity to applaud between songs, and the only interaction discernible with those here to watch him comes when Blumberg lets his brass slide fall to the floor in response to someone at the back’s wine glass falling on its side, not once, but twice (it would turn out to be his out to be his girlfriend’s, something she embarrassedly admits after the show).

Afterwards, I find myself outside with Daniel. In the course of that conversation, he enthusiastically flits from one thing to another – the tour, the next album he’s already working on, the weird topography of Milton Keynes and the fact that he’s off to his nan’s care home the following day to sing traditional Hebrew songs

To the uninitiated, this is pure logorrhoea, a chaotic slew of seemingly randomly-assembled thoughts and subjects; I was fortunate enough to spend the best part of two hours interviewing Blumberg earlier in the year and you just kind of adjust to it after a while; it shows a mind always racing, always thinking, always processing, always crashing ideas together, constantly creating, never still.

‘Off And On’ and another track, ‘Digital’, that the band play turn out to be taken from Liv, recorded by Blumberg, Steiger and Wheatley at London’s Sarm West in 2014 with additional contributions from Seymour Wright (sax) and Kohhei Matsuda (mono synth). Minus was an important album, showing an artist operating at the furthest orbit from where he had been before with bands like Yuck; but, as important and complete it was, it showed Blumberg after his metamorphosis. Liv is an important album as it shows how Blumberg got there, and shows the impact on his affecting songwriting from his time immersing himself into the Café Oto scene with skilled players like those on this album. It illustrates the profound effect that that immersion had on his approach to songwriting: the noise-followed-by-calm methodology is there, but it is perhaps less absolute in its switches from one device to another; it is more interwoven, blurrier even.

Liv opens with ‘Liv’, containing layer upon layer of synth loops, distortion, and impenetrable clusters of compelling, intense noise that suddenly breaks into the enquiry “Who are you that I lived with?” in Blumberg’s distinctive, questing tone. The noise returns, ebbs away and Blumberg’s enquiry becomes “Who are you in my kitchen?” I’m reminded of my own time sat in his kitchen, and I briefly recall how uncomfortable and out of my depth I felt as we started that interview. The track then becomes beatific wordless harmonies, pitched over an antsy, restless bed of sonic shards.

The version of ‘Digital’ included here is more elemental; quieter and more reflective. You can discern a sort of hollow, inquisitive blues poking its way through, the model for the tender songs that would pepper Minus; synth noises whirr and ping around the guitar, as does fluttering violin. It is romantic yet uncertain. “How do I greet her when I’ve been thinking about the other one?” asks Blumberg, his words loaded with pathos. It’s rueful, fragile, uncertain, restless, and speaks to a rift, a crisis, viewed from an otherworldly, out-of-body type of vantage point. ‘Digital’ ends with Steiger’s violin sawing over bird-like sounds, either from Matsuda’s synths or Wright’s sax.

‘Off And On’ begins with hypnotic bass evolutions, tentative synth melodies becoming a stop / start blend of silence and fullness. It’s wonderfully pretty when all enmeshed together, only to become disrupted and expansive. Here you will find hope filtered through strangely uncertain ruminations. Steiger’s violin is here, at times, straight, unadorned, expressive without being taken into angular splinters. Wheatley‘s approach to the double bass is an entirely physical one, being less an instrument and more a box of toys for him to manipulate, pull, scrape, pluck and push its strings to the limits of their tension, and if you close your eyes you can imagine him doing all of that when the players are working their way through this troubled piece.

‘Caught’ is a a long, ‘Madder’-esque centrepiece, Blumberg’s guitar nodding less to inchoate freeform shapes but toward a kind of floating, droning post-rock suite of riffs bobbing up and down over fuzzy distortion and prowling bass. The effect is like drifting along on an uncertain, turbulent sea. It is unswerving in its progress, if a little frayed at the edges, staying there until a tentative vocal appears out of the fog around five minutes in. As ever, these words undeniably mean something to Blumberg, but to the observer, they are impenetrable, suggestive but never definitive; you can interpret the sentiment, but the true impression is elusive, like a fragment of a diary entry of an unknown writer. “Why is this happening?” might be a message of despair or a quizzical, offhand enquiry of some piece of equipment not behaving quite as it should. Around the halfway mark, as the music lurches into a comfortable dirge, Blumberg’s vocal veers toward folksy sung harmonies, a pretty counterpoint to the music elsewhere. Everything stops, falls away, sounding like the end of days in its absence, while the lyrics suggest some sort of harrowing interstitial space in which Blumberg finds himself. Toward the end, the piece lunges back toward a desperate, impenetrable wall of sound in which Wright’s sax bleats and whistles over everything else, briefly.

The album concludes with ‘Life Support’, an accomplished moment of lovely, early Velvets balladry. Here, Blumberg’s folk singer poise and Matsuda’s held tones and splintered half-melodies are underpinned by Steiger’s adaptable playing. Truly transcendent, ‘Life Support’ is a wonder to behold, a towering conclusion to a set showcasing a songwriter undergoing a major transformation and the minus-ing of his craft to where he finds himself today.

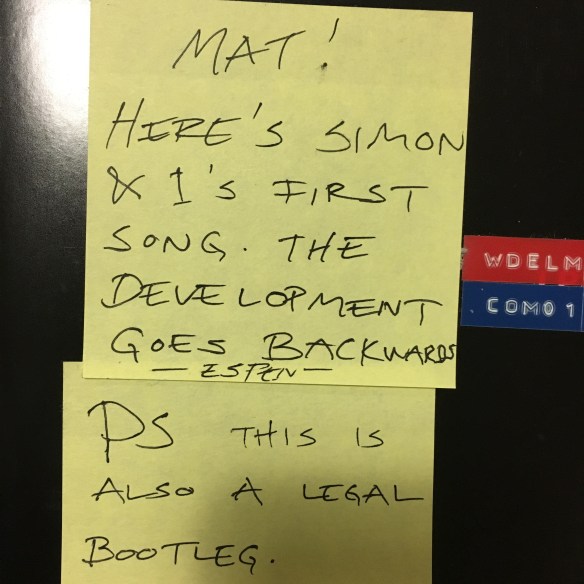

Liv is only available through Rough Trade. Thanks to Paul, Zoe, Joff and DB.

(c) 2018 Mat Smith / Documentary Evidence