![]()

As part of Mute‘s fortieth ‘anti-versary’, the label is making available very special limited edition vinyl versions of selected releases from their four decades of releasing and curating incredible music. To celebrate this element of Mute 4.0, we’re re-posting reviews of those special albums from the depths of the Documentary Evidence archives. Full details on the releases can be found here.

After launching Mute Records with his single ‘TVOD / Warm Leatherette’ as The Normal, few would have expected Daniel Miller‘s next musical move to be an album of (mostly) covers of old rock ‘n’ roll songs. But, then again, if you believed the liner notes Music For Parties by Silicon Teens wasn’t by Daniel Miller at all. Rather, the album was made by Paul (percussion), Diane (synthesizer), Jacki (synthesizer) and Daryl (vocals) and produced by Larry Least (a pseudonym Miller would use again as a producer for Missing Scientists and Alex Fergusson). Eric Hine and Eric Radcliffe provided engineering duties for the LP, half of which was recorded at Radcliffe’s Blackwing studio in London, the location for many early Mute recording sessions.

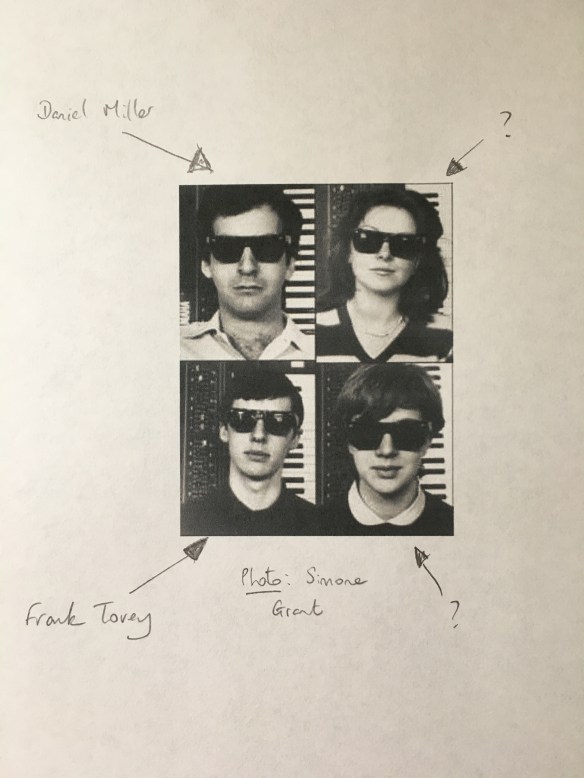

Not having been aware of Daniel Miller, Mute or anything much when this was released (I was four years old), I’m not sure if anyone was suckered in by the ruse at the time – by the time I fell in love with Mute in 1991, the secret (if it ever was one) was already out; Biba Kopf’s Documentary Evidence pamphlet made it completely clear that Silicon Teens was the work of one man and one man alone: Daniel Miller. Apparently, at the time, actors playing the fake quartet would be deployed for interviews. A promotional photo for the group, taken by Simone Grant, included two people whose names are now lost to the mists of time standing in for Diane and Jackie, with Miller and Fad Gadget’s Frank Tovey taking the roles of Daryl and Paul, all four sporting some very Velvet Underground shades.

Anyone familiar with ‘Daryl’s particular brand of singing (nasal, a definite punk-informed delivery) would detect that this was a Miller project from the first lines of opener ‘Memphis Tennessee’; anyone familiar with his electronics work before and after would spot his unique synth work in the chirpy sounds and harsh dissonant interruptions. Anyone who didn’t, but was listening closely to the lyrics of one of the four Miller compositions here, ‘TV Playtime’, may have finally got the connection with the line ‘TV OD, video breakdown‘ delivered in a wobbly voice during one section of that track, while behind the watery voice malfunctioning synths not dissimilar to those deployed on Fad Gadget’s ‘Ricky’s Hand’ flutter and bleep.

To my shame, I only bought this in 2011, though I had bought the album’s three main 7″ singles years before that. I picked up a CD copy of the album from Rough Trade East and happened upon it in the ‘punk’ section; I scoffed at first, until I remembered that when I’d played the version of ‘Memphis Tennessee’ to my dad – an avowed Chuck Berry fan – he screwed his face up in disgust, as if the generally polite sounds of Miller’s version were somehow abrasive on the ears or that making an electronic facsimile copy of a rock ‘n’ roll track was like sacrificing a holy cow; it’s how I’d seen footage of people in punk documentaries reacting to the Sex Pistols, so perhaps Music For Parties was punk after all. Certainly, in ‘TV Playtime’ there is a dimension which evokes the uncompromising sound of Suicide and in turn the pre-Dare sound of Human League at their most uncompromising.

One of my favourite tracks here is Miller’s take on The Kinks’ ‘You Really Got Me’, where the proto-punk / garage rock central riff is replaced with a buzzing synth delivered over a simple motorik beat. If this had been released as a single it could potentially have been chart-bothering, compared with the slightly more bouncy ‘Just Like Eddie’ which apparently did reasonably well as a single. ‘Do Wah Diddy’ and ‘Do You Love Me’ again are brilliant; these were two tracks that I absolutely detested as a child when they cropped up on radio. The latter is frankly among the most manically joyous songs I own, even if it doesn’t start out that way. The album version of ‘Let’s Dance’ sounds like Depeche Mode‘s ‘Photographic’ in its Some Bizarre Album incarnation; like Soft Cell did with their 12″ version of ‘Tainted Love’ mixed with ‘Where Did Our Love Go?’, you almost long for someone to hitch the Teens and Mode tracks together. Irrespective, it’s very danceable, with some quite tasty big fat synth notes as well. The Ramones also covered ‘Let’s Dance’ for their début; when rendered on Ramones as amphetamine-fuelled speed-punk it made complete sense alongside their own ‘Beat On The Brat’, ‘Sheena Is A Punk Rocker’ and ‘Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue’; here too, as a piece of high-energy synthpop, it likewise makes complete sense and the link to The Ramones’ version comes in as Miller snarls the ‘1, 2, 3, 4‘ intro.

Aside from the abrasive ‘TV Playtime’, Miller also contributes three other compositions to Music For Parties. ‘Chip ‘n Roll’ is an insanely upbeat synth pop gem, lots of handclaps and hissing hi-hats, as well as a gloriously twee main riff. It’s like Martin Gore‘s ‘Big Muff’ only way more poppy. ‘State Of Shock (Part Two)’ begs the question as to whether the Mute archives will ever turn up, or indeed if there ever was, a part one; this is a clanking, vaguely dark instrumental track with a stuttering rhythm and some squelchy sounds muttering away in the background. I’m not entirely what party you’d play this at; probably some dark, moody place where you’d be as likely to hear Kraftwerk nestled up alongside Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire. Miller’s ‘Sun Flight’, originally a B-side to the ‘Just Like Eddie’ 7” and included here as a bonus track, is again reasonably dark and mysterious, the distorted chorus intonation of ‘Come to the sun‘ and some snatched radio conversation sounding like a course of action filled will danger, even if the main keyboard riff is singularly both captivating and entirely of its time.

Would an album like this ever get released today? Hardly likely. Music For Parties taps into a sense of kitsch excitement surrounding the relatively (then) untapped potential of the synth in a pop context. Prior to this, and other albums released at around the same time, the synth was mostly deployed by po-faced Progsters with lavish budgets to spend on huge modular synth behemoths. Music For Parties‘ most punk achievement was to take these songs from yesteryear, remodel them as cheeky pop tunes and inject some tradition-baiting lightheartedness.

For Mute 4.0, Music For Parties is being reissued as a vinyl LP.

First posted 2011; edited 2018. With thanks to Simone Grant.

(c) 2018 Mat Smith / Documentary Evidence