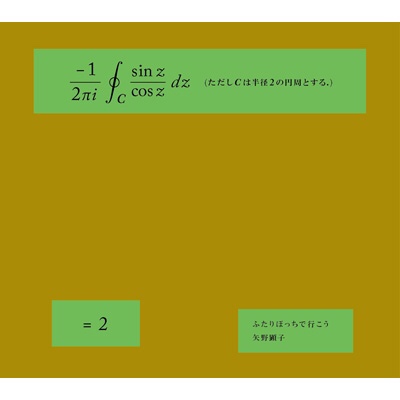

Plastikman ‘Sheet One’ 2xLP NovaMute sleeve.

Released in October 1993 on NovaMute, Sheet One brought Windsor, Ontario’s Richie Hawtin‘s Plastikman onto the label’s roster, Daniel Miller‘s imprint effectively licencing the album for the UK and Europe from Hawtin’s own Plus 8 label.

While Sheet One became notorious for all the wrong (or right) reasons by the CD sleeve’s recreation of a perforated sheet of LSD tabs, with the requisite and implausible rumours that the sleeve really did have acid on it, what’s most surprising is that electronic music designed to be listened to at home or in a club, as opposed to merely in a club, was still a relatively unusual thing twenty years ago. Warp’s Artificial Intelligence compilations (the first volume of which had included Hawtin in his UP! guise) and the series of clever electronica releases clustered around them – such as Polygon Window’s Surfing On Sinewaves and Black Dog Productions’ Bytes, as well as early releases from sometime NovaMute signee Speedy J and Autechre – had paved the way for a new strain of dance music that didn’t require any form of dancing at all.

If Sheet One found itself dropped neatly into that whole Artificial Intelligence genre, it set itself apart by eschewing the notion that these tracks couldn’t be played in clubs. Throughout the album’s eleven tracks, Hawtin maintained a focus on pared-back rhythms more usually found on acid house tracks, perhaps slowed down a fraction compared to the then-popular number of BPMs but not inconsistent with the original tracks by the likes of Phuture from the decade before. Added to that was Hawtin’s love of the key ingredient of acid house tracks – the Roland TB303 – which gave these tracks an energy and vibrancy that most armchair techno seemed to forget to include. Okay, so the 303s weren’t tweaked as hard as Hawtin would do on, say, his astonishing remix of System 7’s ‘Alpha Wave’, but they nevertheless contained enough of a squelchy urgency to get most acid heads excited and if would only take a modicum of pitch-shifting to get these tracks into a more adventurous DJ set.

The other distinctive element on Sheet One, and the element that meant it was able to align itself with the Artificial Intelligence crowd, was the use of reverb. Everything on Sheet One is swathed in rich levels of treacly echo, giving the textures here a languid, atmospheric and vaguely chilling quality. That echoing aspect always reminded me of the eerie static hum that wrapped itself around Kraftwerk‘s Radio-Activity album, and for some reason also made me think of some of the haunting passages on the soundtrack to Teen Wolf. I used to study and revise to Sheet One and its equally-enthralling follow-up Musik, which perhaps credentialises the atmospheric quotient.

In many ways the central track on Sheet One is ‘Plasticine’, an eleven minute epic consisting of a minimal pulse, nervous bass tones and a 303 line that rises up seemingly out of nowhere, bringing with it a more rigid beat and a degree of dark energy. Hearing a 303 like this, where it is presented more or less nakedly, shows just how weirdly versatile Roland’s instrument was – even if it’s being deployed in a way that the manufacturer never intended. A breathy voice that seems to be saying ‘it’s you’ adds to the overall vibe of a haunted, alien dancefloor. ‘Plasticine’ has all the requisite rises and falls associated with most dance music, only here it’s elongated, extended and somehow much more emotionally affecting. The track’s final moments are comprised of deep bass resonances and a thudding remnant of what used to be the beat.

The similarly-timed ‘Plasticity’ is the other stand-out track here, with the sounds of aircraft rumble ushering in a echo-soaked rhythm and ruminative 303 melody. There’s a floating, shapeless quality to some of the other sounds deployed on ‘Plasticity’ – brief melodic pads, clicking, noisy interventions, what might be a euphoric yelp or an anguished scream – giving this a psychotic vibe that would have suited a desperate chase scene in a movie. ‘Smak’ goes even further – a dense web of heavy beats and brooding synths underpinned by strings that evoke comparisons with Laibach and samples of screaming angst.

Any uplifting quality is there offset by a far darker energy, ebbing away into ‘Ovokx’, which reveals the stark message to the world’s population sampled from The Day The Earth Stood Still.

‘Gak’ departs from the regimentation of the 4/4 rhythm and instead opts for a clattering, bass-heavy electro beat draped in layers of cavernous reverb, and double-time percussion that leans close to the skeletal bone-rattling that would come on ‘Spastik’, an effect which is also deployed on the urgent ‘Helikopter’. ‘Helikopter’ really does sound like the rapidly rotating blades of a chopper, layers of hard-spun sound rotating around your ears with an infinite swirl. In complete contrast, ‘Vokx’ is a quiet, stirring cinematic symphony for the scene that surveys the scarred landscape, the second half dominated by sirens, screams and panicked sections of dialogue.

Sheet One is an unsettlingly unique album, and one that knocked its peers out of the park, retaining enough of techno’s key energy rather than disposing with it altogether. Twenty-five years on, it sounds as sharply arresting as it did at the time, while other albums from the time sound positively dull. The follow-up album, 1994’s Musik, was just as attention-grabbing but leaned harder into a more scientifically-assembled experimentalism, highlighting Hawtin’s restless dexterity.

Sheet One was released as a CD and vinyl edition in the UK. There were two versions of the vinyl album, the 2000 copy limited edition picturedisc version of which is now something of a collectors’ item. In 2012 Mute released a remastered Sheet One in the wake of Hawtin’s expansive Arkives 1993 – 2010 boxset, ditching the original NovaMute catalogue reference (nomu22) and replacing it with a Mute one (stumm347).

First published 2013; edited 2019.

(c) 2019 Mat Smith / Documentary Evidence